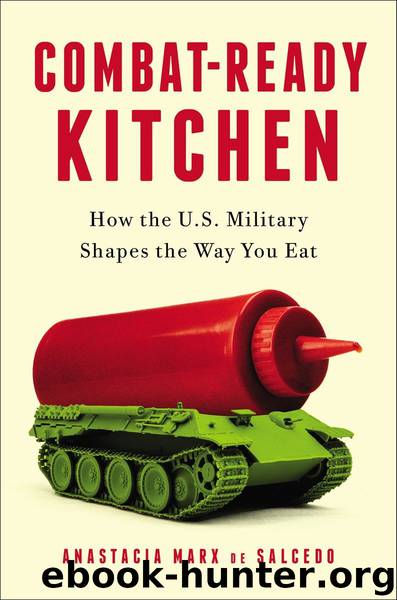

Combat-Ready Kitchen by Anastacia Marx de Salcedo

Author:Anastacia Marx de Salcedo

Language: eng

Format: epub, mobi

Publisher: Penguin Publishing Group

Published: 2015-07-20T16:00:00+00:00

KNOWING WHAT THEY—and what all chemists—knew about plastics, it appears folly that, in the early 1950s, army packaging experts proposed to find a way to heat-sterilize food and then store it for very long periods in plastic wrappers. The three materials humankind had historically used for cooking or storage vessels—ceramic, metal, and glass—soften or melt only at extremely high temperatures (a couple of thousand degrees Fahrenheit) and are either relatively inert, interacting very little with their contents, or have coatings that keep them from doing so. Not so plastic. Most common synthetic polymers used in food packaging soften at 200°F to 300°F, and as far as migration goes—suffice to say that as the molecular equivalent of a plate of spaghetti (the polymer) swimming in sauce (the plasticizer), it’s easy come, easy go. It’s a problem that has dogged the use of plastics in food packaging since the beginning.

In the early 1950s the Quartermaster Corps delivered a wish list to its packaging division: containers that you could manipulate in subzero temperatures, packaging for frozen foods that wouldn’t disintegrate, barriers for dehydrated foods so that water vapor and oxygen couldn’t penetrate them, and rations that wouldn’t be the source of friendly fire wounds and casualties when air-dropped. For a while, each of these problems was worked on separately, but the solution to all quickly converged into one word: plastics. Was it possible to replace the sturdy metal cylinder, which, since the earliest days of canning, had been the favored cooking and storage vessel for moist, shelf-stable foods, with a flexible plastic pouch? In typical never-say-never fashion, the army put their heads down and got to work.

The first step was to review all the available materials and to subject them to conditions simulating that of a retort-processed ration—steam-cooking for three to fifteen minutes at 250°F, random mistreatment, and then abandonment for months. (A retort machine is an industrial canner that subjects multiple cans, jars, or pouches enclosed in a tank to high heat, in the form of hot water, spray, or steam, until their contents are sterilized.) The Quartermaster Food and Container Institute research team, led by Frank Rubinate, quickly found that the best candidate—one that wouldn’t melt, harden, discolor, or disintegrate—was a combination of a layer of vinyl, a layer of aluminum foil, and a layer of polyester film. “It was really a lot of standard packaging techniques, but they had to perform at a greater level of reliability and completeness than before,” explains Rauno Lampi, a food scientist who worked on the project at Natick from 1966 to 1976. “We borrowed from both the canning industry and the flexible packaging industry.”

But from there, the army was stymied—it was a new technology, so to gear up, production capabilities would have to be inculcated in industry. And what better way to do that than to hold a conference, with the lure of revealing the goodies developed for the government’s research program to companies that were always on the lookout for the next big

Download

Combat-Ready Kitchen by Anastacia Marx de Salcedo.mobi

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| American National Standards Institute (ANSI) Publications | Architecture |

| History | Measurements |

| Patents & Inventions | Research |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41995)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(33122)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32796)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18237)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8040)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(7366)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6932)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6929)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6611)

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6433)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(6282)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6267)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6007)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(5750)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5549)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5409)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5369)

Design of Trajectory Optimization Approach for Space Maneuver Vehicle Skip Entry Problems by Runqi Chai & Al Savvaris & Antonios Tsourdos & Senchun Chai(5066)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4996)